Lunch in Stafford services, Birmingham, then down the M5, Cotswolds on the left, the misty Malvern's to the right, early spring greening the hedgerows of the Avon valley. After months of staying local Gloucestershire felt foreign and slightly exotic.

We settled into the Camping and Motorhome site on the outskirts of Cirencester. Never one for changing habits, I immediately performed my usual arrival ceremony which involves an extended harangue loosely based on the Maori 'haka' involving the words 'bungaloid', 'jobs-worths' and 'effing Tories', but whispered darkly though clenched teeth. Very English! Arrival rituals completed, we attempted to take a walk. Cirencester Park adjacent to the campsite looked inviting, a meticulous picturesque landscape belonging to the noble pile on the western edge of the town. It's called The Bathtub Estate or something. It was not to be, Lord and Lady Hoo-ha only allow the great unwashed to wander through their rolling acres between 8am and 5pm, it was now 4.50pm and the wrought iron gates were already wrapped with a chunky chain and firmly padlocked. I channelled my irritation by taking a picture of an inadvertently funny sign fastened to the nearby railings.

I speculated that as medical science and genetic engineering reduce the risks of dying from some horrible disease, in some reforested future the biggest risk to humanity will come from being accidentally brained by a hefty bough. You have to admire the vision of the British aristocracy, The 9th Earl Bathtub is quite clearly well ahead of the game and like all members of his class you can be sure the well-being of the common folk is always uppermost in his mind.

The town's cricket and tennis clubs are next to Bathtub Park (well, they would be wouldn't they!). The junior team's cricket match was entering its latter stages, I suspect it was the first of the season. I am not sure how the parents looking-on were conforming to social distancing, there must have been about forty spectators. They were gaggled rather than distanced. I think most of us are becoming more flexible regarding such matters, we've all had enough. I watched a lanky boy in his mid-teens run-up to bowl, medium paced, well placed, but the shorter, younger batsman had his measure, leaning back he clipped the ball through the covers and ran for two. A small appreciative ripple of applause drifted through the chilly late afternoon air. It was a quintessentially English moment, ok, a posh English moment when someone might exclaim, 'Good show!' or slightly built, effette youths refer to one another as chaps.

I reflected that my youthful relationship with the game had been somewhat chequered. During the summer months three concrete steps next to a patch of green in the middle of the council estate became an impromptu wicket, and a small gang of us kept ourselves out of mischief for weeks with nothing but a toy cricket bat and a balding tennis ball.

However, at Grammar school when faced with the real thing I proved to be spectacularly inept at cricket. With the ball I could easily bowl an entire over of 'wides'; in the field I missed every catch that came my way; at the crease I never overcame the natural instinct to duck or jump out of the way when something solid, the size of a small rock, is hurled towards you at 70mph.

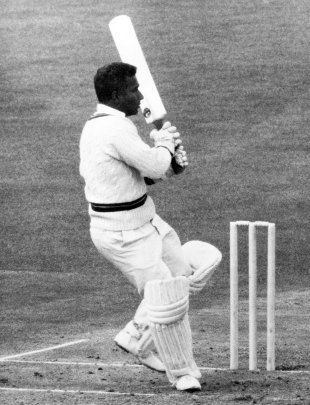

Nevertheless, as boy I watched a lot of cricket . My Dad's weekday job was as a cane fishing rod builder at Hardy Bros., Alnwick's biggest employer. However, pre-war he had trained as a greenkeeper at a Scottish golf club. All his working life, indeed right up into his eighties, he worked part-time as a groundsman, first with the cricket club, then later looking after the greens at the golf course, and finally, when that became too physically demanding, he kept the town's bowling club greens beautifully manicured. Sometimes I used to tag along at the weekend to give him a hand, then watch the cricket. The sight and sounds of Cirencester youth squad in full swing sparked the memory of something I have not recalled for years. By the time I reached my mid-teens I had better things to do at the weekend than to watch the cricket while my Dad waited to roll the pitch at teatime. However, the news that Rohan Kanhai, the renowned West Indian international batsman, would be playing was enough for me suspend my adolescent bookishness for an afternoon to watch the match.

The match between Ashington and Alnwick was always bitterly contested, pitmen versus young farmers, talk about skin in the game! I can't actually remember who won, but recall that Kanhai batted well, but did not quite reach a half century, so a respectable outcome for the home side I suppose. What I do recall is meeting the famous batsman briefly in the pavilion at tea. It was the first time I had met anyone non-white. Unimaginable now and a testament to how the world has become more interconnected and the country far more diveplace during my lifetime. The thing about Cirencester however, is that it strikes you that that is not the case everywhere. No wonder the place reminded me of my youth, because here it felt England had hardly changed at all.

Having failed to go for a walk in the park we decided to take a stroll into town. If you read reviews about Cirencester on Google maps people seem to love it. I suppose it does conform to the version of England portrayed in Downton Abbey or a TV adaptation of Agatha Christie.

The over-riding impression you get of Cirencester is that it exudes wealth, it is not simply slightly posh or 'well to do', but the people here are loaded, like in Monaco or Marbella, but with a more bracing climate. Admittedly, you might argue it has ever been thus. It is one of a string of ancient market town's on the edge of England's southern uplands that grew rich during the late Middle Ages on the back of the wool trade with Flanders. You can see that reflected in the architecture of the magnificent church next to the market place and the timber framed cottages dotted around the town centre.

However, unlike some other Cotswold settlements, Georgian architecture predominates, medieval mercantile wealth superseded by eighteenth century gentrification fostered by the development of the Bathurst Estate on the edge of town.

However, no matter how wealthy the town was in the past it would always have had a mixed population, shop-keepers, tradesmen, servants and farmworkers as well as gentry. These days it is difficult to see how anyone with an average income could live here at all. There were lots of estate agents of the 'Homes and Gardens' variety, most property was over £1,000,000. A tiny one bedroomed terraced cottage in a local village - £320,000. The result is the town centre has the look of somewhere that had been perfected, photoshopped to become a parody of itself, full of up-scale casual wear chains and an Aga cooker shop. I suppose this is not uncommon in the up-market country towns of southern England. What leads you to conclude that Cirencester's is exceptional in this regard is the quietly understated modern office block adjacent to Waitrose and the leisure centre happens to be the headquarters of St. James's Wealth Management, a company founded by a member of the Rothschild family in the 1990s. This not something you are ever going to stumble upon in Carnforth, Sleaford or Chester-le-Street..

Gill needed a garlic and some herbs. The only place open in the early evening was a small Tesco's Express in the outskirts of town, next to what looked like a former council estate. Whereas the rest of the town felt moribund the small store was busy, cars parked randomly on the pavement outside, people queueing dutifully in masks by the door, all kept in order by a fearsome looking young woman wearing hi-res. In the event she turned out to be perfectly lovely, unprompted she offered to help Gill find the herbs. In fact it felt like the first normal encounter of the day.

In keeping with correct Covid etiquette I opted to stay outside, it was just nice to observe normal people doing ordinary things - the Polish woman who had popped out for a bottle wine wearing a startling zebra striped onesie, the sporty looking pair who screeched to a halt in their hot hatch. He looked chunky, a weight trainer probably, but a bit flabby after months of gym closures and a diet of pies. His partner was more svelte in a lycra one piece. Her nails looked like turquoise talons liberally decorated with silver sparkles. It was obvious what her post lockdown celebration had been. For some reason it cheered me up. My advise to a visitor from abroad in search of authentic Englishness - avoid venerable market towns, head for Tesco's.

No comments:

Post a Comment